The Importance of Correct Car Seat Usage:

Implications and Resources for Nurse Practitioners

by Sharon K. Jung, MSN, ARNP, CNRN

|

Introduction

Injuries suffered in car crashes are the single leading cause of pediatric morbidity and mortality in the United States today, accounting for 40% of all deaths associated with unintentional injuries (National Safe Kids Campaign). In 1996, an average of 8 children less than 15 years of age were killed every day, and 980 were injured daily (NHTSA, 1996a). In 1991, over $7.5 billion was spent on injuries to children up to 4 years old after car crashes (Miller, 1993). Correct use of child safety seats--car and booster seats--decreases traffic fatalities by 69% for infants and 47% for children 1 to 4 (NHTSA, 1997); as well as reducing serious injuries by 60% to 78% (Safety Belt Safe, U. S. A., 1996). Observations in local community car seat check up clinics revealed that misuse rates were 80% to 90% (NHTSA, 1996b). If car seats were consistently and correctly used, many injuries could be prevented and more lives could be saved. The purpose of this paper is to explicate the opportunities which nurse practitioners have to provide sound car seat education; dispel the myths surrounding car seat use; identify common errors and explain how to correct them; and provide a resource list for providers and families.

Implications for Nurse Practitioners

Reduction of injuries is a high national priority, and reduction of automobile related injuries is a specific goal cited in the objectives of the Healthy People 2000 document (U. S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 1990). There are several reasons for the unduly high morbidity and mortality involved in traffic related injuries. During a collision, the forces on any child are approximately equal to a child’s weight multiplied by the speed at which the vehicle is moving (e. g., a 15-pound child moving at 30 M. P. H. weighs 450 pounds [15x30=450]). The frequency and ease with which children ride in cars make them likely to be involved in a crash. The automobile provides an easy opportunity for children to move at speeds that are likely to cause severe injury. Most vehicle safety features are designed for adults; and some, like air bags, place children at greater risk for injury. These safety features may lull parents into believing that their children are adequately protected when they are not.

As well as having extremely high mortality, costly morbidity is involved. Frequently, expensive medical treatment is required for long periods of time. Other important factors are the untold human suffering involved when a child is severely injured or killed, as well as the cost to society when bright, capable, young children with high potential become head injured or otherwise disabled children who will need to be cared for all of their lives. During a relatively minor car crash, one child’s superior mesenteric artery was ruptured because of an improperly placed seat belt (Brockenbrough, 1994). The only hope for long term survival was an intestinal transplant. After three years of countless infections and other painful complications, the child died waiting for a donor. Medical care during that time totaled over $1.5 million. Appropriate education most likely may have prevented this costly tragedy.

Counseling in pediatric settings has been shown to decrease the rate of injuries (Bass, et. al, 1993). Nurse practitioners are effective providers of sound and accurate health promotion, because of their ability to assess their clients’ learning readiness and needs, rather than focusing on only the subject being addressed. Nurse practitioners also have been shown to spend more time with their patients (Maraldo, 1993). In one study (Geilen, 1997) involving a sample of pediatric residents, well child visits were audiotaped to document how much time was spent doing injury prevention counseling. Results of that study indicated that an average of 1.08 minutes was spent addressing health promotion issues during the visits. It was also observed that only 60% of the residents allowed feedback from the parents whom they were teaching.

Nurses are more likely to consider the characteristics of the learner during patient teaching. For instance, some parents may be impressed with the cognitive aspects of the issue. Teaching the crash dynamics equation may lead these learners to change their behavior. Others may respond more to the emotional side of the issue. The most effective way to teach them may be to tell a story and show pictures of a family impacted by a tragedy caused by failure to use a car seat correctly. Still others may change their behavior when they are made aware that there may be legal consequences if they do not use their car seats appropriately. This author is personally aware of parents that have been charged with manslaughter for failure to have their children buckled up.

Sound, appropriately delivered and reinforced health promotion is likely to result in long term rather than short term behavior changes. The best way to produce sustained, high quality performance in any situation is to tap into the internal satisfaction which learners derive from knowing that they have done well (Kohn, 1995). Further, external rewards motivate learners to get the rewards, not to do the tasks correctly, and the positive behavior created by the reward will cease when the reward is no longer available. That theory was supported wherein an incentive program was designed to encourage people to wear their seat belts and buckle up their children (Foss, 1989). The results showed that car seat usage increased slightly during the time period in which the rewards were being given, but quickly fell to the pre-study level after rewards were no longer available. By clarifying common myths, as well as showing people how to avoid common mistakes, nurse practitioners are in a position to help their clients reap the benefits which internal satisfaction provides; such as increased bonding, self-esteem, and greater security obtained by high level safety practices.

Common Myths

Many parents believe that they do not need to place their children in safety seats for short trips. This practice is strongly discouraged for two reasons. Seventy five percent of all crashes occur within 25 miles from home, and at speeds posted at 40 mph or less (National Safe Kids Campaign). Because of the crash dynamics, there is little or no safety margin for inconsistent or incorrect use. Children only may need their car seats once, but during that once, they need them 100%. Also, children will become confused by inconsistent car seat use and are much more likely to rebel if they are not required to ride in the car seat for every trip.

Many parents believe that adjustable 3-point seat belts are an appropriate and safe alternative to car seats. The adjustable style is common among recent vehicle models, and is designed so that the top anchor point moves up and down to adjust the shoulder portion of the seat belt. While this option may provide a better fit for small adults, it is inadequate for children until they are about 5 feet tall. The placement of the shoulder belt may be improved, but the hazards caused by the seat of the vehicle are unchanged. Children typically slouch forward on the passenger seat to be able to bend their knees. Such action raises the lap belt from the pelvis to the mid abdomen level, potentially endangering any or all of the abdominal organs. The iliac crest does not develop until a child is approximately 10 years old. Consequently, the lap belt does not reliably stay below the iliac crest, and can contribute to abdominal injuries (NHTSA, 1997).

One trend in our society seems to want children to grow up faster, which motivates many parents to move their young children to a more advanced level before they are the appropriate size and weight. Infants are frequently moved to the forward facing position of their car seats when they should still be in the rear facing position; placed in booster seats before they have outgrown their convertible seats; or are placed into the adult seats far too soon. Passenger seats are designed for adults, not children. It has been estimated that safety belts alone offer a 29.5% fatality reduction for small children, compared with the 47% reduction which car seats offer (Miller, 1993).

Many people perceive that car seat laws reflect "best practices". Barraged with confusing or

conflicting information, parents or child care providers often look to the law for guidance in

making their decisions regarding when to stop placing their children in car seats. Parents do

not realize laws are a series of compromises, and may reflect a minimum, rather than a high safety standard. Currently, car seat laws are enacted by the individual states; some only addressing infants, and others requiring children to ride in approved safety seats until 4 years of age. (SafetyBelt Safe U. S. A., 1996). It is important for health care providers to be aware that the

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) now recommends that children ride in approved child safety seats until they weigh 60 pounds, and ride in the back seat of the vehicle until they are 13 years old, whether or not there is a passenger air bag. Children are 26% less likely to be killed when riding in the rear seat than children in the front seat. (NHTSA, 1997).

Many parents perceive that shields provide a greater level of protection than the 5-point harness. All styles of convertible car seats must pass the crash tests before they can be sold. However, if parents choose to use a convertible seat in the infant position, they should use a seat that has a 5 point harness, rather than a shield, because the infant can slide behind the shield, increasing the possibility for injury in the event of a crash (NHTSA).

|

|

5 - point harness. |

Common Errors

There are several common errors made during safety seat use (NHTSA). While correct use is addressed in an instruction booklet that comes with any car seat, there may be many reasons why parents do not follow them. If parents need new instruction booklets, they should call the car seat manufacturer and request them.

Incorrect fit of the harness

Parents leave too much slack in the harness. To effectively secure a child, allow only 1 finger breadth between the child’s shoulders and the harness. Children not snugly secured in their seats have suffered head injuries and even been ejected from the vehicles in which they were riding (Graham, Kittredge, & Stuemky, 1992). Bulky clothing can prevent a snug harness fit. In cold weather, parents should place children into their car seats in indoor clothes, then place a blanket over them to keep them warm. The harness retainer clip should be placed at shoulder level to keep the straps from falling down upon the arms.

|

|

| Incorrect use. Too much slack. Parent can pull the harness away from the child. Plus the baby can play with it. |

Correct Use. Only one finger breadth between the child and the harness

|

|

|

| Incorrect use. Incorrect placement of the harness clip down at the child's lower chest / waist area. |

Correct Use. Proper use of the harness clip, at the level of the child's shoulders.

|

Incorrect angle of the car seat

When infant or rear facing convertible seats are placed onto any vehicle seat, they must be placed so that an infant rides at a 45-degree reclined angle. Most automobile seats are not flat; and placing a rear-facing seat into the automobile seat may force a child into an angle which is too upright. To correct this problem, parents can place tightly rolled towel(s) underneath the car seat to level it. A newborn was asphyxiated and died on the way home from the hospital because the child was riding upright, allowing the airway to become occluded (Pennsylvania Chapter, American Academy of Pediatrics, 1995). No car crash had occurred. The hospital and nurse were found liable, because the nurse placed the baby in the car.

|

|

| Incorrect use. Baby is too upright. |

Correct Use. A towel under the

seat boosts the angle to 45 degrees. |

In contrast to infants, toddlers need to ride upright. If toddlers are in a reclining position and there is a collision, their crotches will absorb the impact of the crash.

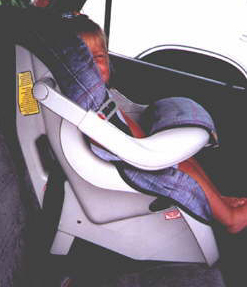

|  |

Incorrect use. Seat in the reclining

position and forward facing. |

Correct Use. The car seat is in the

upright angle in the forward facing position. |

Incorrect threading of the harness

In the rear facing position, the harness needs to be at or below the level of the baby’s shoulders. The harness holds the infant down into the seat.

|

|

Incorrect use. The harness is above

the baby's shoulders in the infant position. |

Correct Use. The harness is below

the level of the infant's shoulders. |

In the forward facing position, the harness needs to thread through the top-most slots unless the manufacturer instructions indicate otherwise, to take advantage of the reinforced plastic to support the heavier child.

|  |

Harness threaded through the top slots. Observe the thickness of the plastic at that level, the car seat needs that strength to sustain a heavier child in a car crash.

|

The back of the car seat with the harness in the lower slots. |

|

|

|

Incorrect use. The harness is in the lowest slots, clearly below the level of the child's shoulders. |

Rethreading the harness into the top slots. |

Incorrect placement of the car seat into the vehicle

When a car seat is placed into a vehicle and the seat belt fastened around it, it should be secure and not move any more than 1 inch from side to side or forward on the vehicle seat. If it moves more than 1 inch, the seat may tip when the car goes around a corner, and/or fail to hold the child in place in a crash. To obtain a secure placement, parents should press down on the seat with their weight and pull the seat belt taut. If the seat is in a lap-shoulder belt position, it may need a locking clip. A locking clip fastens the shoulder and lap belt together to hold the lap part tightly around the seat when correctly used. Parents should check the owner’s manual of their vehicle to find out whether they need a locking clip; and if not, how to pull the seat belt taut.

|

|

An example of a seat tightly secured into a vehicle. |

Failure to correct a recall

Parents should register any new seat with the car seat manufacturer and inform the company of a new address if they move. Some recalls correct relatively minor problems, while others are for problems, which could result in serious injury or death if not corrected. To find out if their seats have recalls parents should call NHTSA’s Auto Safety Hotline at 800.424.9393.

Failure to replace parts and pieces if they are lost or damaged

All parts and pieces are important to car seats. If lost or broken, replacements can be obtained from the manufacturer. Using safety pins to replace metal slides or wooden bars to replace metal ones could be deadly.

Placing children in the front seat

If possible, children should ride in back seats until they are at least 13 years old. Children sitting in the back seat of any vehicle have a 26% lower fatality rate than those sitting in front seats (NHTSA, 1997).

Failure to replace a seat which has sustained a crash with a child occupying it

All car seats should be replaced if they are involved in a crash with the child riding in them. The plastic shell and the harness absorb the impact of a crash only once, and cannot be guaranteed a second time. Most insurance companies pay for a new seat as part of repairing the vehicle. Parents must be advised to contact their insurance agents and explore that possibility.

Used seats

Used seats may be acceptable if financial constraints make the purchase of a new seat difficult (Safety Belt Safe, U. S. A., 1996). If parents choose this alternative; they need to obtain the instruction booklet, make sure that all of the parts and pieces are there, reliably find out the history of the seat, and check for recalls. If it is impossible to learn whether the seat has been in a crash, it should not be used. There is no way to tell by looking at a seat whether it has, or has not, been in a crash. Most manufacturers recommend replacing seats after 5 years.

Conclusion

The American people now have many choices as to whom they will seek to provide their primary care; they can choose between nurse practitioners, physicians, naturopaths, osteopaths, and physician assistants. Insurance companies also make choices as to which groups they will reimburse; as well as deciding how much, for varying groups. Nurse practitioners have been shown to spend more time with their clients, and can capitalize on their communication strengths to make even better use of their injury prevention counseling. If nurse practitioners take advantage of their abilities to practice the positive aspects of both the nursing and medical models, it will increase their credibility, as well as enhance their position as primary care providers. A strong and sound knowledge of car seat usage, as well as the ability to impart the information effectively to families served, can help increase the health of individuals, families, and society.

Resource List

Air Bag & Seat Belt Safety Campaign

1025 Connecticut Ave., NW

Suite 1200

Washington, DC 20036

E-mail: airbag@nsc.org.

Car Seat Manufacturers

Century 800.837.4044

Cosco 800.544.1108

Evenflo 800.233.5921

Fisher Price 800.432.5437

Gerry 800.525.2472

Kolcraft 800.453.7673

Governor’s Highway Safety Office - call directory assistance in your state

National Safe Kids Campaign 202.662.0600

National Highway Transportation Safety Administration Hotline 800.424.9393

References

American Academy of Pediatrics, Philadelphia Chapter, American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Blvd., P. O. Box 927, Elk Grove Village, IL 60007.

Bass, J., Christoffel, K. K., & Lindome, M., et al. (1993). Childhood injury prevention counseling in primary care settings: A critical review of the literature. Pediatrics, 93 (92), 544-550.

Brockenbrough, M. (1994, June 12). Tough little kid is facing risky, rare transplant. The News Tribune, B1, B2.

Foss, R. D. (1989). Evaluation of a community -wide incentive program to promote safety restraint use. American Journal of Public Health, 79(3) 304 -306.

Geilen, A. C., Mc Donald, E. M., Forrest, C. b., Harvilchuck, J. D., & Wissow, L. (1997). Injury prevention counseling in an urban pediatric clinic. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 151, 146-151.

Graham, C. J., Kittredge, D., & Stuemky, J. H. (1992). Injuries associated with child safety seat misuse. Pediatric Emergency Care, 8 (6), 351-353.

Kohn, A., (1995). Punished by rewards. New York: Houghton Misslin.

Maraldo, P. J. K. (1993). Politics and policy in primary health care. In: M. D. Mezey, D. O. McGivern (Eds.). Nurses, nurse practitioners: Evolution to advanced practice (pp. 342-370). New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Miller, T., Demes, J., and Bovbjerg, R. (November 1993). Child seats: How large are the benefits and who should pay?, in Child Occupant Protection, Warrendale, PA: Society of Automotive Engineers, (pp. 81-90).

National Highway Transportation Safety Administration, Traffic Safety Facts, (1996a) National Center for Statistics & Analysis, Research & Development, Washington, D. C., 20590 [http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov]

National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (1996b) Observed patterns of misuse of child safety seats. Traffic tech. NHTSA Technology Transfer Series, 133. Safety Belt Safe U. S. A.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (1997) Standardized Child Passenger Safety Program

National Highway Transpiration Safety Administration, Are you using it right? NHTSA.

National Safe Kids Campaign. Motor Vehicle Occupant Injury Fact Sheet [www. safekids.org.]

Passenger Safety Education Materials. Safety Belt Safe U. S. A. 123 West Manchester Blvd. Inglewood, CA 90301.

U. S. Dept. of Health and Human Services (1990). Healthy People 2000. Washington, D. C.,

Last updated: July 8, 2000

Use of this section indicates you agree to the Terms of Use.

Copyright 1994-2003 NP Central

|

|